There are possibly only two examples of my great grandfather’s handwriting. One is a signed letter written in 1914 and addressed to Beaty, his eldest child, this bears the letterhead of the Seaman’s Institute in Sydney, Australia. Harry was a regular letter writer and although I doubt that this was the last letter that he wrote, I’m certain that it is the only one that has survived.

In November 2018, I stayed at the Holiday Inn Hotel in the area of Sydney known as ‘The Rocks’. Across the road, opposite the hotel’s main entrance, is a building bearing the name the Rawson Institute for Seamen. In 1914, Sydney would have looked very different, no harbour bridge, no opera house, but there would have been parts of today’s Rocks that would still be recognisable. In 1914 the Rawson Institute was the Seaman’s Mission, and this, judging by the letter heading, is where my Great Grandfather wrote the letter that his daughter cherished so much that she kept it for the remainder of her life.

The Rawson Institute backs onto Circular quay, where today the world’s largest cruise liners dock. In 1914, SS Cevic, a livestock carrier capable of transporting up to 1,000 cattle, could have moored here. Although not comparable in size with modern ships the Cevic was one of the largest merchant ships of its day. My great grandfather, Seaman Harry Robert Linfield was on that ship and during his brief stay in Sydney he stayed at The Seaman’s Mission.

The SS Cevic belonged to the White Star line and during its time prior to 1914 there were a couple of notable records concerning it. Cevic had a deep draught, which would justify it docking at Circular Quay. In 1910 it had attempted to get through the Suez Canal where it had grounded, become damaged, and was taking in water which meant that it had to return to Port Said for repairs. Its second notable record is that on 20th April 1912. It had been on the North Atlantic route and reported the siting of two icebergs. This was six days after the sinking of the Titanic. Harry was not on the Cevic on either of these occasions.

The SS Cevic would soon return to Tilbury in the Thames Estuary. Back at Harry’s home at 47 Mandeville Street, Liverpool his call up papers were waiting for him, instructing him to re-enlist in the Royal Navy. He was 46 years old.

This is the letter that he wrote whilst at the Sydney Seaman’s Mission, It is addressed to his eldest daughter Beatrice, who was a nurse working in London.

I have retained Harry’s grammar; he would have left school at an early age with only a basic education. In March 1884, at the age of 17, he enlisted in the Royal Navy. His handwriting is neat and stylish and reading his letter I feel that it is written in a similar way to how he would have spoken.

Dear Beat,

Just a line from your loving father hoping that you are quite well and happy, was more then glad to hear that you are getting on all right and that you had got your uniform now. I hope and trust that you will be a good girl to your mother for I know that if you do all that she as taught you, you will not be far out, for she is an angel on earth and no soul on this earth can say that she as ever done wrong or can point the finger at her and if you only follow in her footsteps you will be all right.

I had a letter from your dear mother and she told me a lot and I am very proud of you so you must cheer up and don’t be down hearted for this is a very funny world and we never know what dangers awaits us but we must trust in the dear Lord that rules and foresees every thing and ask his protection and we know when I shall be home this dreadful war has upset everything. We were going to carry troops and horses but it is all cancelled now and I don’t know what we are going to do but as soon as I do I will write and let your dear mother know. I have written three letters and I have received one, but that is no fault of your mothers. She told me that you were going to write to me but I am afraid that your letter has been captured by the Germans but if so I can overlook it as that would be contraband of war. You must know that if I come to London I shall come and see you as our ship lays in Tilbury Docks and I can easily come and see you if it is Nov.

I will drop you a line and then I shall know that you will be on your holiday I must now conclude dearest daughter with fondest love to you and when you write to mother tell her I send a kiss through you so goodbye and God bless you and keep you from harm. God be with us till we meet again Beaty dear.

From Your Ever Loving.

XXXXXX Father,

XXXXXX H R Linfield

There is some subtext in the letter which I do not understand the background to. Beaty never married and seldom spoke about this part of her life. She passed away in 1994 at the age of 99.

One of the things that I find profound about Harry’s letter is his faith. At the back of the Seaman’s Mission is a chapel and although the Rawson Institute is today a beautiful restaurant, the chapel is still there and has been kept in immaculate condition. Amongst the windows of the Chapel is a one dedicated to the Rev Charles Henry Moss for his 28 years of work on the staff of the Sydney Mission to Seaman, he died in 1915 at the age of 52. It is most probable that these two men met and maybe shared their faith with each other. There is also a Window in the chapel dedicated to British sailors who served in the 1914-1918 war.

Today, the chapel is used for weddings. I’d like to thank François, the current owner of the building who showed my wife and I the Chapel and the rest of the building.

I wonder what my grandfather’s fears were, a long sea voyage, storms in the southern ocean, the threat of war?

It is possible that the Cevic may have transported horses from Australia because around this time the Australian Light Horse Regiments were posted to the Middle East to fight against the Ottoman Empire. They went on to see action in Palestine, Syria and modern day Turkey.

On Robert’s approach to and departure from Sydney in 1914 he would have sailed along Australia’s southern coast. SS Civic would have followed this route regardless of whether it sailed via Cape Hope or the Suez Canal. Eight days and a thousand nautical miles from Sydney he would have passed the Cape Otway lighthouse, an important landmark for all sailors following this route. This was to be his last trip as a Merchant Seaman. On his return to Britain he re-enlisted in the Royal Navy.

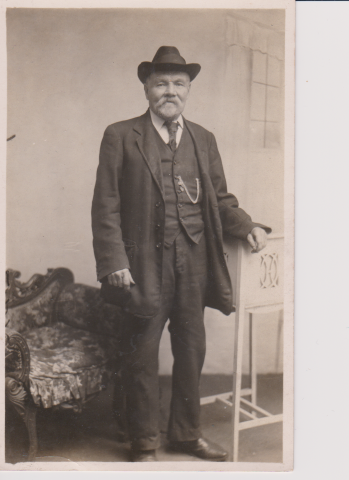

Returning to Tilbury, Harry made the twenty mile journey into London to meet Beaty. Some time prior to this he’d had a photograph taken at the Henry Bown Studios, 400 Evelyn Street, Deptford, south east London and he probably passed that photograph to her the last time she saw him.

In 1915 the Scottish trawler Loch Navar was in Dover, it had been seconded by the Royal Navy and was being used for minesweeping duties in the English Channel. Under cover of darkness, German submarines would lay mines in the waters outside British ports. On the night of Friday 16th April the dock was full and ships and boats that were double and triple moored. Sailors returning to their ships often had to run along damp planks of timber placed between the ships. It was not uncommon for sailors to miss their footing and fall into the water. That evening, as a blackout covered the port, returning to his ship, Harry slipped. I don’t know whether he could swim; certainly fully clothed and wearing boots with nobody nearby to help, survival would have been a struggle.

In June his body was recovered from Dover’s Granville dock. He had been in the water for six weeks. He was identified by a tattoo on his arm and the remains of a tobacco pouch found in his pocket, both were recognised by the Dunedin born, New Zealander, Captain of the Loch Navar, Edward Butler.

On May 13th 1918, His Majesty’s Trawler Loch Naver was sunk by a mine from the German submarine UC-74 (Wilhelm Marschall), near Mandhilou Point in the Aegean Sea. All 13 hands on board were lost including Captain, Edward Butler.

At the beginning of this post I wrote that I believed that there were two examples of Harry’s handwriting; the other is a handwritten prayer in the front of a Bible. I believe that the Bible may have been his, the handwriting is very similar. The written date in the Bible is 1890 and Harry’s Navy records indicate that, at that time, he would have been 22 years old and serving on HMS Collingwood, an Ironclad Battleship and part of Britain’s Mediterranean Fleet.