Last year I thought a lot about the Great War. I thought about my two grandfathers and my great grandfather. If my grandfathers had not survived that war, then I would certainly not be here.

Readers of my earlier postings will know that last year I wrote about Wilfred Owen, the war poet, killed in action during the early hours of 4th November 1918.

In one poem, Owen uses the words of the Roman poet Horace, written before the birth of Christ, ‘Dulce et decorum est, Pro patria mori.’ These words can be found in many places. They are on the base of the war memorial in the Garden Village at Port Sunlight. They are in the Chapel at the Royal Military College at Sandhurst and in the US, at the Arlington Memorial Amphitheatre. Doubtless, they can be found on many other cenotaphs and war memorials around the world. A loose translation from Horace’s Latin, these words say, ‘How sweet and honourable it is to die for one’s country.’

In Wilfred Owen’s poem he calls theses words for what they are.

Dulce Et Decorum Est by Wilfred Owen

Bent

double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame, all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of tired, outstripped Five-Nines that dropped behind.

Gas! Gas! Quick, boys! – An ecstasy of fumbling,

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time;

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime …

Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams, before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues, –

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

On Armistice Day 2018, my wife and I arrived in Melbourne, Australia. It was one hundred years, to the day that marked the end of that war and also the day that Susan Owen, Wilfred mother, received that fateful telegram. That morning I thought about that knock on the door.

In Melbourne we were met by and stayed with our friends Barry & Pauline Kelly and a couple of days later, when they were showing us around the city, they took us to see the State of Victoria’s, Shrine of Remembrance. This impressive monument was designed by the architects, Phillip Hudson and James Wardrop, both had fought in the 1914-18 war and both had enlisted here in Melbourne. After the war they designed this monument in the classical Greek style. The building was opened in 1934 as a tribute to Australians past and present who sacrificed their lives protecting those freedoms that we hold dear.

As we entered the Sanctuary I saw magnificent carvings lining the walls depicting Australian servicemen. In the centre of the entrance hall a marble stone is sunk into the floor on it is carved words taken from John 15:13 ‘Greater Love hath no man’. The roof of the building had been designed to let in a shaft of light that would focus on the word ‘Love’ on the 11 hour of the 11th day each November.

We climbed the steps to the external gallery surrounding the top of the building. In the bright Australian summer sun we looked out across the remembrance gardens, parkland and approaches that surround the monument. To the north we could see the tall buildings of Melbourne’s business district including the Eureka Tower that we had visited shortly after our arrival.

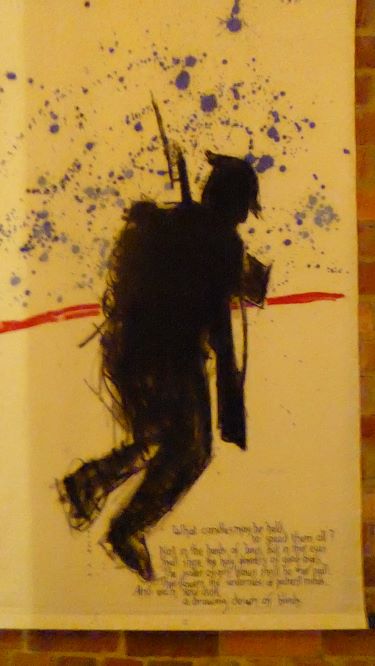

Coming down from the roof and passing the entrance hall we descended to the crypt which contains a permanent display of wartime and Australian service exhibits, artefacts, medals and memorabilia. But first, we had to pass through the hall of columns. Here, in the subterranean half-light and in stark contrast to the daylight outside hung calico banners bearing images of war, images depicting northern Europe one hundred years earlier, silhouettes of soldiers, tanks and barges. The exhibition was the work of Melbourne Artist Craig Barrett and was called Everyman, named after the Siegfried Sassoon war poem of the same name.

Wilfred Owen’s poetry was here also and I instantly recognise: Hospital Barge at Cerisy, Anthem for Doomed Youth and Dulce et Decorum Est. I have known this poetry for most of my life, yet here, in the atmosphere of the crypt and accompanied by Craig Barrett’s artwork it had found new life and new meaning. A picture is said to be worth many words and this is true of Craig’s artwork. These are powerful words and Craig’s art adds to the poetry of both Sassoon and Owen. These words in this place seemed even more poignant. It maybe just me, but finding Owen’s words along with this artwork effected me. A cold shiver, a presence, whatever it was; this was the right words alongside the right pictures in the right place. At that moment, Wilfred Owen could have been beside me.

The people who had actual physical contact with those who lost their lives in the Great War have all gone. Craig and I are of a similar age, and our generation will be the last one that will have actual memories of Great War survivors. Siegfried Sassoon lived until September 1967 so his timeline overlaps our own.

Craig, originally conceived the banners as a “one off” three month art installation for The Hall of Columns, and they were originally displayed there in 2005. Since then, he has gifted them to the Shrine and they have displayed them every couple of years in the run up to Remembrance Day and through until the end of January. This year, however, they extended the display to 30th April.

I’d like to thank Craig Barrett for providing me with information and giving me permission to show the photograph of his work . For a better view of his work, please see the photographs which can be found on Craig’s website.

http://www.craigbarrett.com.au/shrine-of-rememberance/h

Another website, most certainly worth a visit is that of the Shrine of Remembrance. https://www.shrine.org.au/Home